This is my 20th year as a member of an international film union best known as IATSE, which is an acronym for a 4-mile long run-on sentence describing what its members do and the incredibly specific places where they do them. It’s my theory that nobody actually knows all the words in the actual title of the organization and instead just make up something, hoping that nobody calls them out on their bluff.

Now, I’ve been meaning to make a post to commemorate this anniversary but it’s been a tough year for my family and my mind had been on other matters until this morning when I saw something on the internet that made me angry (which I firmly now believe is what the internet was originally intended to do).

The specific sentiment of the post that got my goat implied that our union was not instrumental in the creation of Georgia’s film incentives; that we simply assisted the state legislature, which is just a terrible lack of understanding of how the events unfolded.

And I guess that’s what really motivated me to sit down and knock out my thoughts in my blog, because I want these younger members to have the truth in their hands when they speak about what went before them. So little information about the history of our local has been preserved in writing that something I still consider to be a recent event has already passed into the realm of legend, lore, speculation, and worst of all: misinformation.

My friends over at Oz Magazine are currently working on an issue that will document the history of the tax incentives from many perspectives in the Atlanta film community, and I absolutely look forward to reading those interviews, but until that issue hits newsstands I feel compelled to share my own memories in this personal blog post.

First of all, let me explain how and why I joined the union.

I started as an intern for the prop department on Robocop 3. I kept the truck neat. I loaded blanks on gun days. I stacked swords. I made artwork for on-camera props. And most importantly, every Friday I would take a big folder full of cash and make a run with a teamster to the liquor store to stock up the giant beer cooler at the back of the prop truck for wrap beer. I also began learning things like set etiquette, and why we should all appreciate Teamsters.

I’m very fortunate to be able to say that by the end of that show I assumed the job of third props assistant, thanks to the departure of my friend and mentor Dwight Benjamin-Creel, who had left to be propmaster on a movie of his own. I would eventually leave Robocop prior to wrap to join Dwight on his show.

My resume had several film and television projects on it before the older folks on set urged me to join their union, Local 479. Together with Propmaster Joe Connolly I was sworn in, standing in the middle of North Avenue while shooting a never-to-be-seen pilot starring Danny Baldwin. I remember going to my first union meeting at some restaurant (maybe a Bennigans?) with Joe. We didn’t recognize ANY of those people from the sets we’d been working. Not a one. And all of them were complaining about not getting work. I still remember the moment that Joe and I turned to look at each other like “who the hell ARE these people and why aren’t they working?”. That was when I first learned that there would always be a group of people who might not get hired as much as others.

By the end of the 1990s work was growing scarce, even for those who had never had trouble finding jobs. Most camera department carts had stickers with a circle drawn around a Canadian maple leaf and a big strikeout drawn across the leaf with the words “Runaway Production” emblazoned alongside it. Canada was taking all our jobs.

In truth, Canada was mostly taking jobs from Hollywood, but we all supported keeping the business in the states because we were friends with people from Los Angeles and many of us aspired to work there someday. Some of our local crews already held cards in those California unions and California’s lost work was brought close to us because of our relationships with those men and women; our friends.

By the time Louisiana’s tax incentives were firing on all cylinders our work had trickled to a stop. Those who could find work outside the state began traveling. Some moved from Georgia to Louisiana or to Los Angeles, like my dear friend and prop-brother Joe – he needed to take care of his family and it was the only move that made sense. I wish that I had followed suit.

But those of us who were unable or unwilling to move began getting part time jobs around town in order to remain solvent.

My old propmaster friend Dwight was unable to negotiate with producers to bring me in as his second on these out of town shows and at that point I realized that I should never rely on one person for the security of my work and I learned to fend for myself. Since few people would be likely to need an out-of-state assistant propmaster I began taking jobs as set designer and even as a double-secret art director. But these jobs were small and new work did not take their place quickly when the shows wrapped.

By 2003 it was apparent that our local was dying.

Louisiana’s tax incentives were like a black hole that pulled in any projects bound for the southern states. It must have been a golden age for our colleagues in Cajun country, but the unfortunate side effect of their success was our certain demise.

General Membership Meetings were no longer filled with unknown whiners, they were filled with set dogs that I had worked with for years – people I had fought alongside in the trenches, from construction to wardrobe. And like me, they were all struggling, financially. I may write this more than once over the course of this blog post, but it was a painful time.

By this point we had been meeting in the North Room of Manuel’s Tavern for a number of years – the concept of owning our very own union hall wasn’t even on our radar.

The door to the North Room would be closed when the meetings started, and the Sergeant at Arms actually had to guard that door from entry by drunken bar patrons, partying outside. The walls of the North Room weren’t thick enough to block out the noise of football games, birthday parties, or the occasional crash of breaking dishware. It sometimes sounded as if there were a saloon brawl happening out there, with cowboys breaking chairs over each others’ heads.

At some point our union officers began enforcing the rule that disallowed the consumption of alcohol during meetings, which came as a terrible blow for some of us. It was the first hint that civilization was coming to our wild and woolly proceedings, and I’m sure that there are a lot of union members today who would only attend our general membership meetings if beer were provided to soften the grinding deadly boredom of the endless proceedings, though if that were to ever happen there might need to be a warning that “union meetings may lead to alcoholism”.

Now: I need to say that our meetings had been contentious in the past.

In one meeting I yelled at our regional IATSE representative, Scott Harbinson, in a discussion about Savannah being awarded to Local 491 in Wilmington. Never mind that I had never worked in Savannah and that I did not understand the business decisions at play and did not know the politics involved, I simply felt that it was wrong for another state to control Georgia territory. Note: yelling at somebody (especially an officer) in a meeting today will get you escorted out of the union hall. They’ve gotten all fancy like that.

A lot of us 20+ year members remember being incensed when Mike Akins moved us from an external company’s health/savings plan back to the International’s plans. It would take me more than a decade to look back with perspective to see that he probably made that unpopular move to repair our local’s estranged relationship with the International. Some have chosen to forgive Mike, some have not. It was a divisive issue with a lot more complexity than I’m prepared to write about today, and more senior members like Susan VanApeldoorn are better suited to describe the events that had precipitated the initial move away from the union’s plans.

But back to our dying local.

I still remember the meeting when Mike Akins and Bobby Vazquez began outlining the plan to form an alliance between Local 479 and the Georgia Production Partnership (GPP). This new entity would be named EDGE, which stood for Economic Development through Georgia Entertainment.

By uniting the forces of Atlanta’s film industry we would hire two lobbyists, one a Democrat, the other a Republican, in the attempt to get tax incentives passed for Georgia, to compete with Louisiana’s monster incentives. (And as meager as our local’s holdings were back then, I’m told that Local 479 was the primary financier of the first efforts of EDGE).

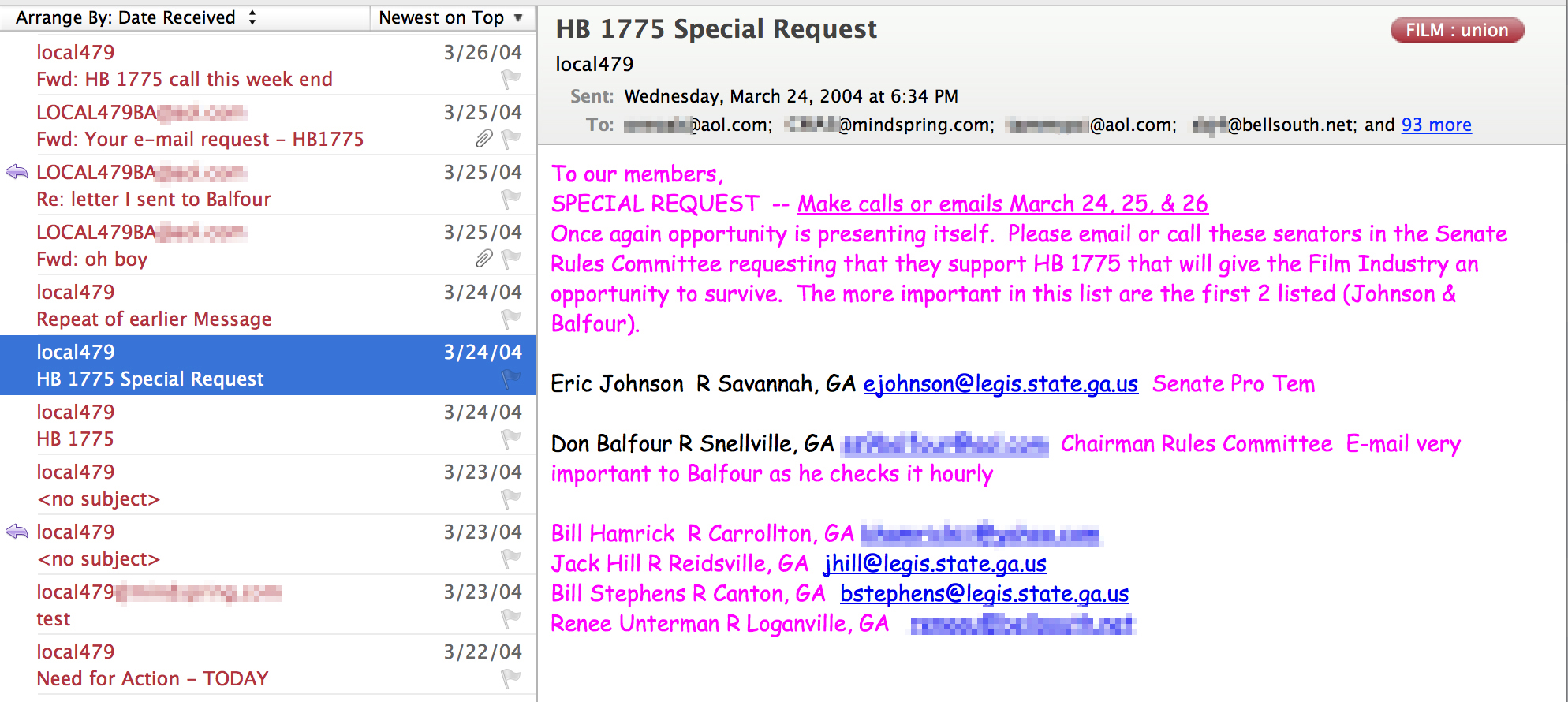

Email campaigns were organized and messages began flying out between the local and its members, and between friends in other organizations, from Greg Torre (the Georgia Film Commissioner at the time) to Oz Publishing to the Georgia Production Partnership and a variety of producers around the city. Our numbers were small, but we worked as a team – our spare time was spent on the telephone and writing emails.

One of the early mobilization emails implored us to voice our support of House Bill 1523 to the members of the Ways and Means Committee…

On Monday, March 8, 2004 at 2:59 PM from Local 479:

URGENT! URGENT!

Opportunity has presented itself again. We need to make calls to representatives and senators and urge them to support House Bill 1523. Send e-mails or telephone calls to members of the Ways and Means Committee to please pass HB 1523 out of committee. We have only 4 (four) days left to get this bill out of the committee so that it can ten go to the floor and then go to the senate.

The body of that email listed contact information for all 18 committee members (which I’m not publishing here on the web because some of those contacts listed personal phone numbers and email addresses).

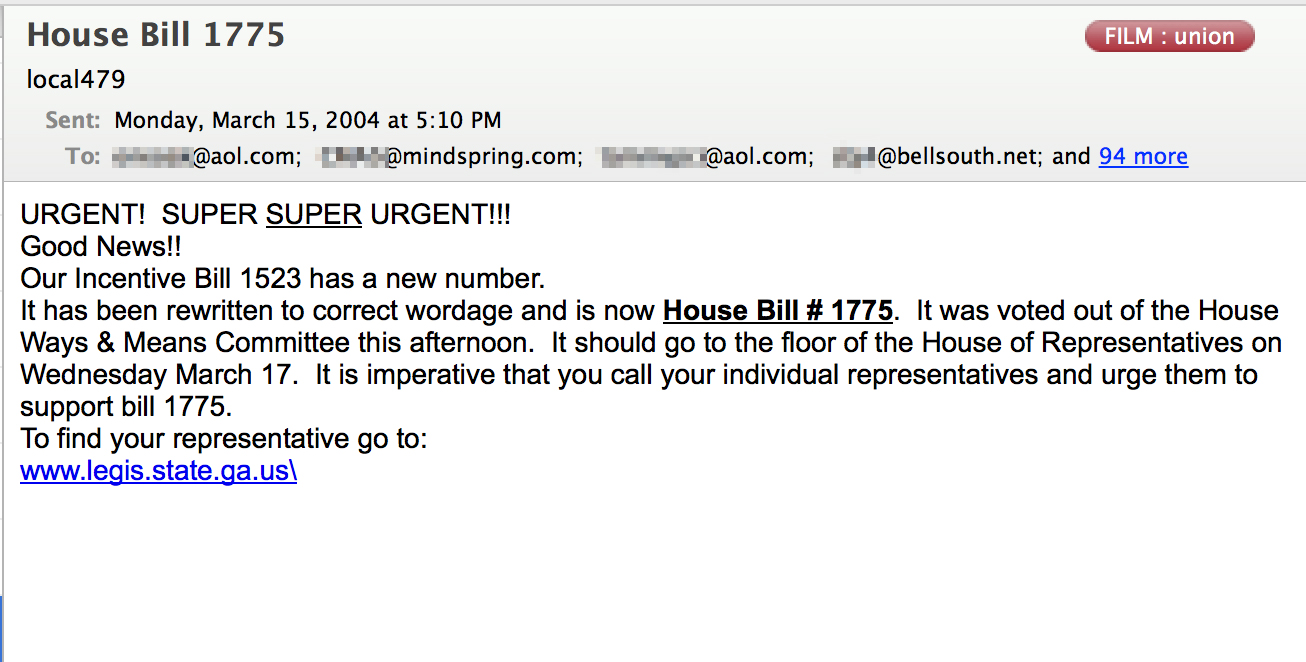

And then the bill changed numbers.

Another email arrived in my inbox two weeks later explaining that our bill had moved on to the Senate Rules Committee, and highlighted which legislators should be our top priority for making our case for our industry. Our primary targets were identified as the Senate Pro Tem and the Chairman of the Rules Committee. This was of course all new to us, and most film crews are neither writers nor politicians, so some of them relied on canned messages prepared by the office.

On March 24, 2005 at 3:39 PM a message was sent from Local 479:

Our incentive bill (HB539) will come up for a vote in the full senate tomorrow, March 24. If you have not yet contacted your senator you should send them an e-mail and urge their support of this bill.

Like everyone else I wrote emails to a lot of legislators. I still have some of those letters.

I also went to the capital a few times during the session to see the process in action. Mike Akins was there every time I went, following the lobbyists around the capital. He was always ready to step into a meeting to answer their questions about our industry, labor unions, and and how important the film industry could be for the state’s economy. Every time I went I hoped to see the bill discussed down on the floor but I never did see that occurrence. More than anything I saw what a bazaar the capital is when the legislature is in full session. It’s crazy busy.

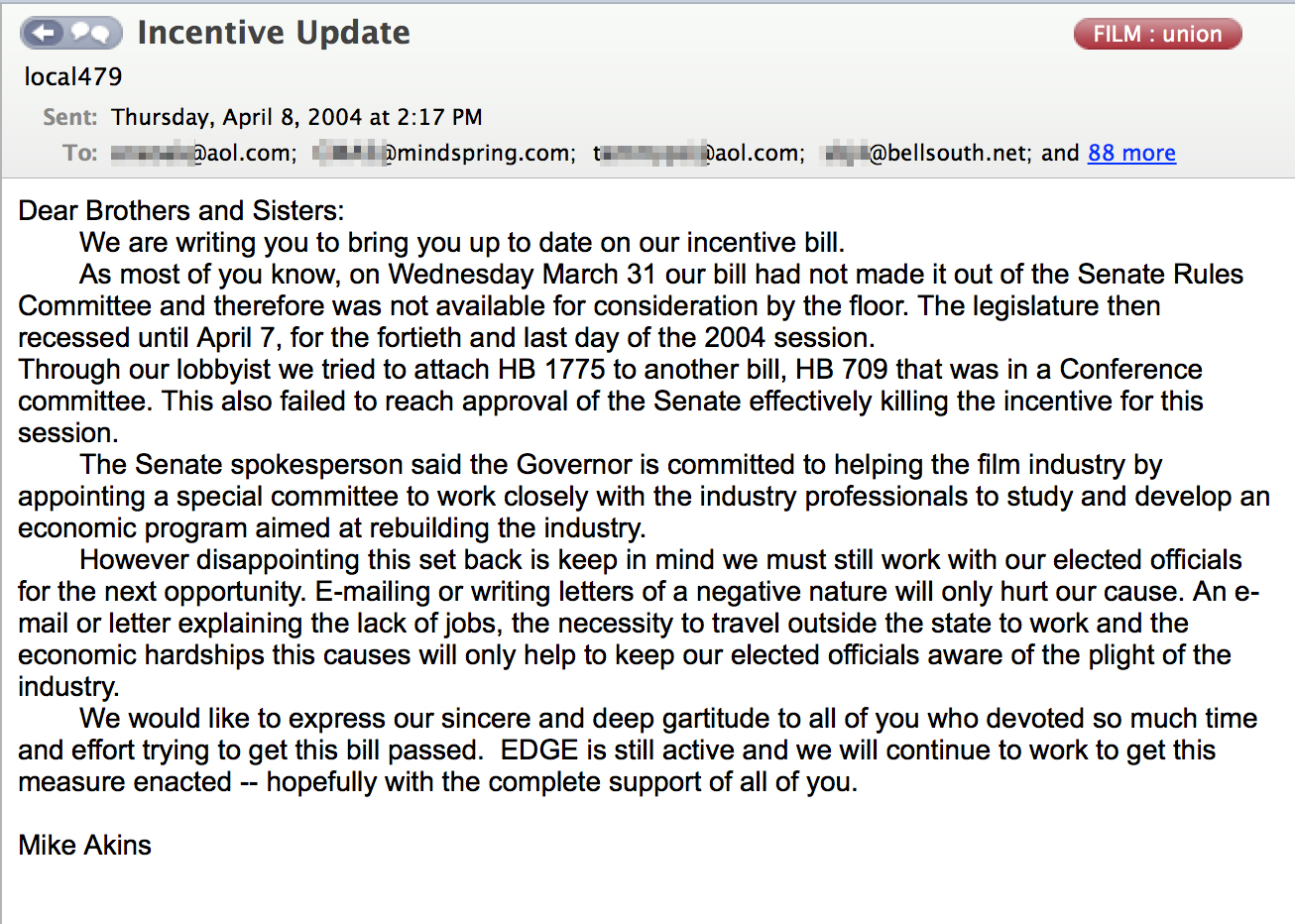

Ultimately, HB539 failed to pass.

However, it did get the attention of Governor Sonny Purdue, and the very next year a bill went forth into the legislature with the strong endorsement of a lot of our state’s legislators, and in ensuing years that same support for our industry transferred over to Governor Nathan Deal’s administration and those of other state legislators.

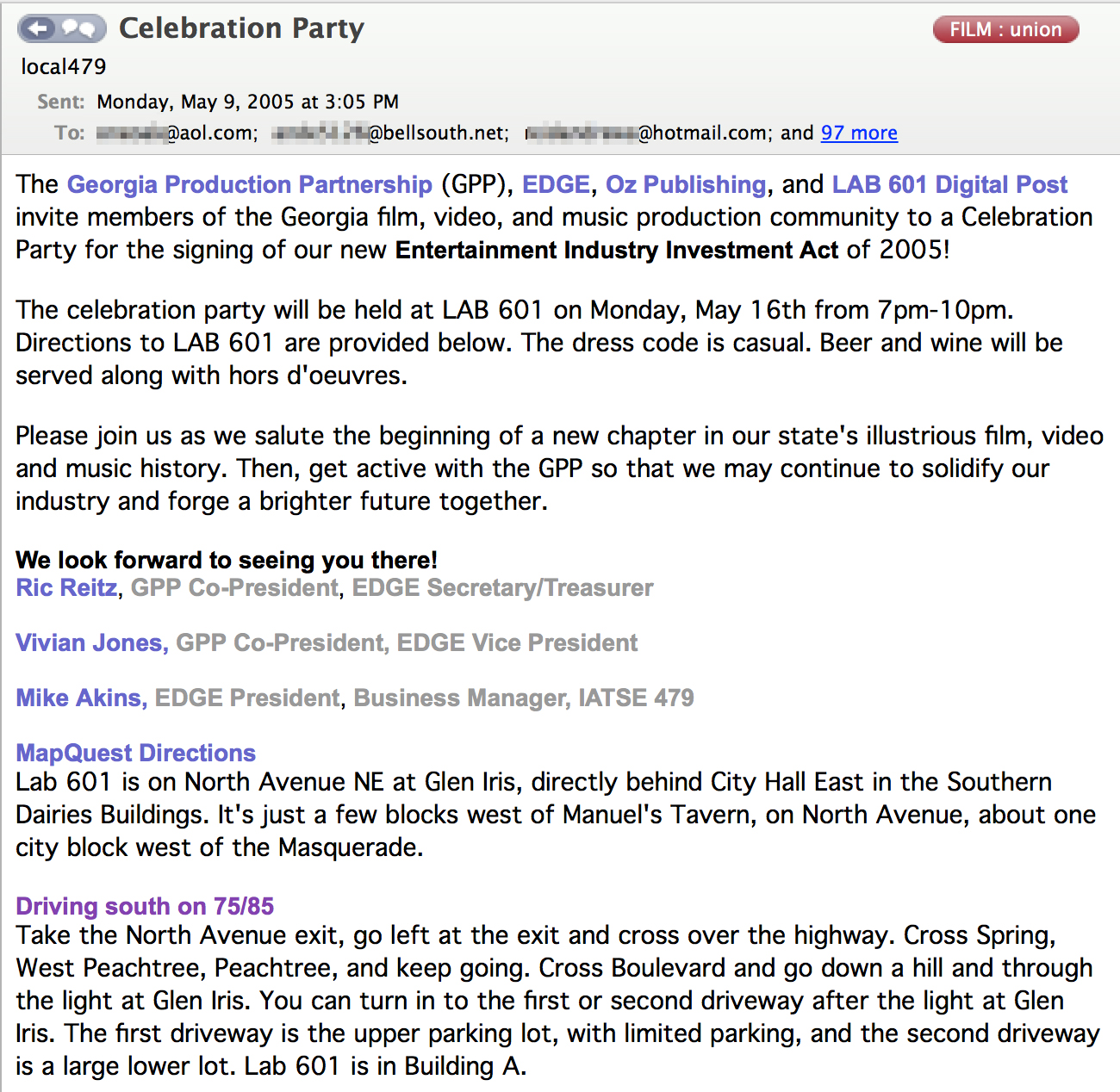

There was a big party to celebrate the win at Lab 601, Pete and Dave Ballard’s editing house.

Sadly, I was not able to hang on until the bill’s passage in 2005.

Instead, I accepted a marketing position with an architecture/development firm that I had been consulting with on and off between shows since the mid-1990s and in the years since I have learned firsthand how investors tend to be “risk averse”, which simply means that they avoid investing into unstable environments.

Even if I had been able to hang on, the effects of the tax incentives would take several more years to fully kick-in and begin delivering a steady stream of work to our state.

The tax incentives I fought for now benefit a new generation of Atlanta film technicians. Some have blossomed from the new work and are always busy. Some struggle to put together enough days to make it worth the fight. We were never guaranteed of work prior to the incentives and to perceive them as a guarantee of employment now is a big mistake that no one should make. The only thing that the tax incentives do is to create an environment that is conducive to being hired. The final gap between potential and actual employee is up to each person’s personality, skills, and resume – and I hope you are all able to get a spark to leap that gap.

In the years since the implementation of the tax incentives our state and local leaders have proven themselves to be able to provide the kind of stability that attracts the big business of Hollywood. The studios are not coming to Atlanta (as I once thought) because we are good and clever, they are coming here because we have been affordable and predictable, and our organized labor works hand-in-hand with a legislature that has been traditionally anti-union.

That’s some pretty crazy stuff right there – like cats and dogs living together.

There is some sentiment among some of my very best friends that they would like to see some sort of protectionism built into future editions of the tax incentive, but as attractive as that idea may be to them, I’m quite certain that it holds the potential for dooming Georgia’s industry by limiting the flexibility of producers to assign the personnel they want to their projects. I remain convinced that open source is the model that has proven most stable for the business and that the moment any of the elements slip too far out of alignment is the moment that a new generation of film crews will be forced to write letters to their representatives or to travel out of state to keep making movies.

Atlanta’s very unique collaboration between labor, government, and the studio system has garnered the attention of the world.

This September, Oz Publishing hosted the 40th Annual Cineposium right here in Atlanta. This event was organized by the Association of Film Commissioners (AFCI), who hold this symposium in a different country every year. This year they arrived in Georgia with the goal of understanding and replicating our success in their own home locations.

So, going back to the original online conversation that spurred this never-ending post, the state tax incentives did not just have “help” from us, they were initiated by our community and realized with the guidance and the leadership of two Governors and a large group of Georgia legislators who understood our vision and acted to make it a reality, for which we should all be thankful.

I hope that folks who were here in Atlanta during the time when we stood on the brink of extinction will share this post to their preferred social media channels and that they will share their own stories about this period in our history.

Note: I believe that I have obscured all email addresses in the posted screen shots, but if you spot one that’s not a public address please let me know and I’ll update the image(s) as necessary.